16th of February – 8th of March, 2024

Preface

This post turned into something of a bête noire. It’s been half-finished for over two weeks, and at one point was 6,000 words; meandering, disjointed and esoteric. The result is not quite what I had in mind; it still meanders and has as many loose ends as Hampstead Heath after dark, but the process of writing it, re-writing it, scrapping it, and finally pulling it out of the bin, was a helpful lesson in itself.

I was often left considering what the point of this blog is. It’s a travel blog with a bit of personal nostalgia thrown in, was my first thought–mainly for my family and close friends. Do people want to read highly personal thoughts and opinions? Probably not at the surface level, but perhaps there’s some value in sharing deep reflections and themes. Interpretations that someone may be able to find some connection with–some help, even. And the personal journey is really what this whole trip is about.

Perhaps most importantly, in the future, I too will be the reader.

Introduction

I’m done with sight-seeing and (relative) roughing it. I’ve unashamedly come on a beach holiday in Costa Rica to escape the grind of travelling. Three weeks of surfing, yoga and meditation. This is also the time I’ve given myself to work on my plan. The–where do I go next–plan.

These answers aren’t just going to fall out of the sky in some mystical, cathartic epiphany whilst I’m sitting on (or running towards) an Incan toilet. I’m going to have to strip myself back and work for it. Albeit whilst sitting by the beach.

It’s a two-day journey from oxygen-deficient Cuzco, and I’m mildly amused at the respiratory relief I feel in the stale aeroplane atmosphere. On good authority, I have bypassed the capital, San Jose, other than a forgettable night in a hotel airport. The connecting flight from the Costa Rican capital to Nosara is a short propeller-plane ride out to the Pacific coast early the following morning.

I’m excited about this. I’ve never been on a propeller plane before, but I have entertained loose thoughts about one day learning to fly. It doesn’t disappoint. Take-off feels worryingly improbable, but once we’re airborne, it’s glorious. Above the majestic view of the Pacific coastline, my thoughts and feelings are mainly sitting with the mechanical experience of the tiny plane. It’s analogous to driving a manual sports car or riding a motorbike; you’re as close to the drama as it’s reasonable to get. With each sphincter-loosening twist and bollock-bruising bump; each pocket of air or hollow in the tarmac, the energy is fed back through your seat (or hands), directly into your nervous system. A pure analogue experience that–assisted by Brian Eno and John Cale–eventually moves me to tears. When we land, I’m straight on the phone to my friend, Eva (who flies), about lessons when I get back to England.

Sat at the back grinning like a child.

Upon arrival at an airport not much larger than a London bus stop, it’s nowhere near as humid as I expect for a tropical jungle. But the heat. It takes some getting used to. This is Dry Jungle; one of the rarest climates in the world. It’s also one of the world’s Blue Zones; a term not without controversy, I discover[1].

On the recommendation of a couple of friends, I’ve chosen to base myself in Nosara, a small town around which beach communities–mainly Playa Pelada and Playa Guinoes–have built up. Development is set back from the beaches to protect the wildlife (mainly the turtles); and institutions in the town, such as the Bhodi Tree and Blue Spirit, are world-famous, yet purposefully secluded. And surfing, almost everyone I meet surfs.

Nosara Beach, as seen from the mountains.

It’s particularly popular with Americans, and post-pandemic has become a favourite of the remote worker as a semi-permanent home to escape winter, or a stop-off for the digital nomad. Prices are more Malibu Beach than Bournemouth Beach, but the cost buys you peace and anonymity. There are A-Listers in the line-up[2] at dusk (apparently, I didn’t notice), and no one could care less. I’m assured that parties do happen but behind the curtain. To quote Withnail[3]: ‘free to those that can afford it, very expensive to those that can’t’.

My Yoga practice is not up to much. All the running, rugby, football, etc. over the years has left my muscles tightly wound (I’m also beginning to understand it’s where I store my stress), and whilst my warmup and recovery are now carefully considered, for most of my life, they were non-existent. For the best part of a decade of club rugby in London, for example, post-match recovery on a Saturday was a quick shower and eight pints (minimum).

Gladly, I have shifted my pace of life since then–or life has shifted me–and yes, my yoga practice is formative, but it’s progressing. In Nosara, I sign up at Nalu. The studio is a sheltered wooden floor, has no walls and is enveloped by a carefully cultivated garden in the shade of Kapok and Caoba (mahogany). A collection of living jewellery – Monstera, Elephants Ear, Asparagus Ferns – adorn these majestic trees. Even in the intense midday heat, the arboric shelter propagates a deeply soothing atmosphere. I attend wonderfully thoughtful yin and vinyasa classes almost daily.[4]

I take to walking along the beach in the late afternoons and swimming at sunset. On one of these walks, I meet an American surfer, Lucia. We get chatting; Lucia runs her own media business, lives in Nosara during the US winter, and Venice Beach, LA, for the rest of the year. We have a peculiar amount in common and agree to meet up to surf later in the week (I may have overplayed my hand). She also invites me over to her place later in the week to meet some of her friends.

Evening walks; a touch better than a lap of London Fields before bed.

There’s a well-known Mexican shaman in town (of course there is) and Lucia asks me if I want to meet her for an aura cleansing later in the week. Sure, I say; sounds refreshing. This is not my first encounter with a shaman, and I’ll leave most of it out of here as it got very personal, but the unanimous shamanic verdict thus far is that my spirit animal is an Eagle[5], but not one who is currently flying. “Why [she says, looking me in the eye and gesturing to the floor], do you flap around on the ground and not soar above the trees?” One to ponder.

Aztec eagle, plus friend.

One of Lucia’s friends, Franciso, is the custodian of a finca (farm) in the hills above the town, where he and his team are undertaking a project to oversee the re-growth of Dry Jungle in lands previously cleared and over-farmed. He invites me up there once Saturday afternoon to have a nose around. Franciso is Costa Rican but read his Masters in Regenerative Economics at Schumacher College in the UK[6]. We spend the afternoon discussing his studies, various British idiosyncrasies (health and safety; warm beer in pubs; apologising for things that aren’t our fault) and flaws in both of our country’s socio-economic policies. His review of UK National Parks, in particular, makes me laugh “I went to one once, and I asked when will we get there, and my friends said ‘we are here’, and I said, but where are all the trees? There are just fields of grass and sheep.”

Surfing

In one of the great surprises of your week, you’ll no doubt be shocked to read that I was the only guy in town surfing in Speedos–I didn’t see another soul strapped into a pair in my three weeks in Nosara. I’m not trying to create a spectacle[7]; I just want to feel the water unencumbered by superfluous material.

Having grown up a swimmer, and therefore impervious to swimwear trends, I’m almost always to be found in water in my smalls. But a trend for Speedos does occasionally come around, yet always in an ironic and (frankly), cowardly, way. I’m entrenching myself in this defensive position because when others fell by the wayside and succumbed forever to the safe harbour of the board short, I pushed through. Through teenage ridicule, university incredulity and twenty’s reluctant acceptance. It is now something those who know me well would associate me with, deeply. If I died tomorrow, it wouldn’t be inappropriate to bury me in a pair. Sure, sometimes I’ll throw on a pair of shorts (if we have a posh lunch to attend to, for example), but it is very much the exception. If it sounds like pride, it’s not; it’s authenticity. There’s dissonance when I throw myself into a body of water in anything other than my Speedos (see the Amazon River).

Author (in SPANKS) with Evan, on Neil’s boat, somewhere off the coast of Southern Spain, c. 2004.

Beyond sartorial conservatism and (by extension) the merry-go-round of cool, I don’t understand why more men don’t insist on swimming in Speedos. You won’t find many women flailing around in the water in shorts. And for good reason; it’s no fun whatsoever and it’s not remotely practical. And the dead straight leg, or baggy style do nothing for the shape of men’s legs or bottoms. As a man with awkwardly large quads and a backdoor you could balance your breakfast on (but certainly wouldn’t want to), perhaps it’s a practical point – Speedos are for comfort.

Author (in same set of SPANKS) playing Boules with John, somewhere in Andalucia, c. 2007.

Anyway, I was talking about surfing. I’ll try and keep the practicality and jargon to a minimum, but in short: when you’re learning to surf, you spend most of your time in the whitewash, where the wave has broken and is advancing towards the shore in an even line. It’s nice and gentle and you learn to pop up, stand and put in a few basic turns. The next stage, which is a significant step up, is to head out beyond the point where the waves break, or outside. (Logically, therefore, inside is any point between being outside and the shore). Unless you are purposefully heading in, or riding a wave, you do not want to be caught inside. And crucially, directly inside is the impact zone. You really don’t want to be found here unless you want a repeated pummelling.

Having set this scene, it’s hopefully clear that getting outside – especially with a longboard[8] – is not only imperative, but a challenge. Waves tend to arrive in sets – usually 7/8 – directly following which, you have small window of calm to paddle like mad to get outside. On top of the relentlessly advancing waves, there are the tide (high better than low), currents (some helpful, most not) and wind (offshore, good; onshore bad; too strong in either direction, bad) to consider. I’m not a fucking oceanographer, I mutter to myself, as I paddle out with Lucia late one afternoon, taking a couple of waves in the face on route.

Once you’re outside, the real work begins–wave selection[9]. Couple this with the complex social structure of the line-up, and you’re hopefully getting a sense of why surfing has one of the flattest learning curves in sport.

A surf fan club of one having his own problems with conditions in South West London.

But the rewards–see Maitencillo post–can include exhilaration and transcendence, the like of which I know few other ways of achieving–naturally aspirated or otherwise.

Just getting outside and sitting in the line-up can give you a sense of connection rarely achieved day to day. With the off-shore wind behind you–stealing a line from one of Lucia’s essays on surfing–the spray off the top of each passing wave, literally, showers you in rainbows. To take that simile a little further, the prisms of brine crash around you like an acid-induced downpour of Storm Thorgensen design. Following this psychedelic cleansing, there is an instantaneous peace on the far side of a breaking wave. You’re deeply aware of the thunder rolling behind you, and you’re at once delighted not to be part of it and excited to continue on your path.

Bobbing up and down like a buoy (or is it boy), I was too busy being captivated by these deep and mixed feelings of relief and satisfaction to notice a vast wave creep up on me; luckily, I was (just) outside, but its passing motion rolled me over. When I resurfaced, spluttering and clinging to my board, Lucia looked at me, raised an eyebrow, smiled softly and said ‘cute’. Needless to say, this was the opposite of what I was going for.

Not the author, but a usual pose following take-off.

Midday is not a good time to surf in Nosara, especially midday on Thursday the 7th of March; aside from the tide and the wind, the sun was raging. As my instructor had said to me earlier in the week–stay out for more than 20 minutes at noon and you’ll get cooked. Three weeks in, though, and my back is inured with a leather-like quality. And I’m stubborn. There’s a fine line between stubbornness and stupidity, I am aware, but whichever side it happened to fall on my final day in Nosara, I was rewarded. Despite the chop, a northerly current and an onshore wind, smaller waves were breaking closer to the shore–ideal for someone like me. I found the right take-off points on some soft lefts and caught a couple of shoulders. What a rush. But, I now understand why (as a regular rider), I’m really looking for the rights. Surfing backside, which is akin to a backhand in tennis (I suppose, back-arsed might be a better way to describe it), is tough. You’re blind to the wave and constantly craning your neck to work out what line you should be taking, and where you should put in a turn.

One especially aggressive wave forced my Speedos up my crack on take-off, and I briefly surfed it ‘thong-ed up[10]’. Perhaps it is this–I realised, as I tried to avoid a pummelling in the impact zone whilst attempting to extract the material from my arse–that renders Speedos impractical for surfers.

A journey within

Travelling alone, sitting with your feelings, taking an honest hard look at yourself can be tough. Especially when you commit to ignoring the dopamine-drenched comfort blankets of smart phones and alcohol. And there are many days over the three weeks in Nosara where I struggle with it, but this is the point, I keep telling myself; this is where the work lies. With the usual escape routes sealed off, my only option is to turn and face.

I am meditating twice a day, surfing every day; I am running, swimming in tropical seas at dusk; I even made some friends[11]. But I am also sitting squarely with some of my most painful memories, and it can be excruciating.

I could treat this like a holiday, settle into the moment and stop thinking. But what would I learn?

Stripped back of the safety nets of routine; the comfort of family and friends, and of familiarity, I feel raw and deeply vulnerable. But this is a perfect opportunity to make better sense of myself and I am determined to understand what these pains are trying to tell me – there is information here.

A psychedelic experience one evening in my tree-top apartment renders me prone on the floor, sobbing, and convinced that I am nothing but organic matter slowly succumbing to the powers of the jungle–crawling with malevolent bacteria and parasites, my weakened immune system the only thing between me and my body subsuming into the earth.

Religion and connection–a quick detour to 1992

It’s a cliche as threadbare as my current pare of Speedos to compare surfing with religion. So, I will try not to fall too far down that particular crack, but I understand why it’s tempting. Surfing can provide a connection that is perhaps often missing from modern life.

In the late 19th Century, Nietzsche declared that God was dead. And predicted the subsequent onrush of Fascism and Communism into the void that religion left. The shape of the void was what people instinctively seek–connection, often via rules and structure that tell them what to think and what to do. Thankfully, we’ve seen extremism off (mostly, and for now), but what, therefore, is left? Without Religion, I think we each have a personal responsibility to solve our connection void.

I bring this up because these three weeks in Costa Rica have left me pondering what sort of hole my Atheism has left me, and what, if anything, I could fill it with.

“Faith can be very, very dangerous, and deliberately to implant it into the vulnerable mind of an innocent child is a grievous wrong.”

Richard Dawkins

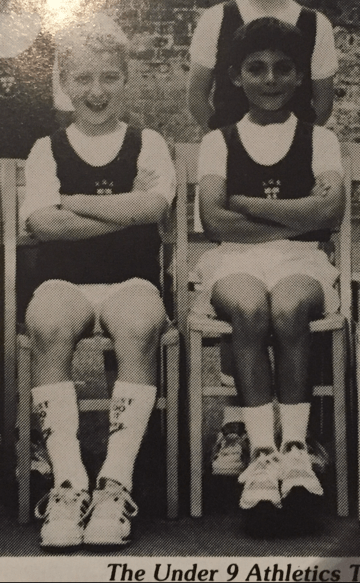

My earliest memory of being aware of the power of Religion is from around eight years old at, school–the RGS Newcastle–roughly 100 years after Nietzsche made his famous proclamation. I had an openly Christian teacher[12], and I was highly sensitive to the inconsistencies and coercive tone in her teaching. I sensed she was pushing someone else’s agenda, and I couldn’t hide my dislike for her, or her bullshit stories. It was her patronising manner, too, as if she was in possession of some great truth, that poor little me was tragically blind to. Even more galling was the ‘there, there; you’ll understand soon enough’ pat on the head that would kibosh logical interjections. Fuck her and her piousness, I thought[13]. I’m going home to play with my Lego and boot a football against the wall until it gets dark. (Perhaps if we had lived near an ocean with a decent break this is where surfing could have crept in and started to fill the emerging void). My antipathy towards Religion started here–an incredulous child who was, in one classroom, being taught that our understanding of why boats float came from Archimedes and his displacement theory (which I could get on board with); yet in another room, without a hint of metaphorical dilution, that one man, 2,000 years ago walked on water and we should therefore bow down to this.

Author (left) at eight, in the school athletics team; mostly interested in running around as fast as he could, but already making enemies in high places.

This is an important reflection, because whilst I am not questioning my Atheism, even a subconscious rejection of a greater authority at a young age perhaps created a void that I have been unaware of for years.

I have revelled in the contrarian role (Nihilism is a rational response to the human condition etc.) for years–dismissing most forms of authority to a fault. Cynical of humans wielding power and too busy dismissing what cannot be true, did I harden myself from opportunities to exist more effectively within social structures and form wider connections?

This is now probably getting a little too Baroque, but something has shifted in my perspective whilst pontificating on this.

Conclusions

We talk a lot about living in the moment–that’s where peace and happiness lies, we’re told–but, if you want to work on yourself, to make positive changes, you have to go back and dig things up–sift through the trash to find the hidden gems. By definition, that is unpleasant, but can also reap priceless results.

So, what next? Beyond making money to pay the bills, or filling my days in Hackney–reading, tending to my bonsai and drinking coffee–how will I ensure connection in what I do?

I’ve started by setting some personal values. If I align these to my choices, I reason, I will find authentic connection. From this can come greater self-esteem, a deeper focus and–hopefully–a better human being in the world. Or so the logic goes.

As an exercise to translate all this theory into practice, I undertook the Japanese exercise of Ikigai[14]. I recommend doing this if you’re planning on making any changes.

On the flight out of Nosara, I reflect on how my interpretation of wave formations has changed irrevocably. Beyond the whitewash and algae blooms, I can only count one surfer on their board bobbing around outside. It’s almost midday.

[1] I noticed in San Jose airport that Blue Zone is now being packaged up and marketed. ‘Buy this honey, or that chocolate bar and you’re tapping into the Elixir of Life’. It unapologetically implies.

[2] The group of surfers you see bobbing about beyond the breaking waves. A complex social structure.

[3] On reflection, I can’t think of a more incongruous character for Nosara than Uncle Monty.

[4] One of my usual yoga studios in London, for example, is overlooked by an office where a chap sits stoically in front of his three screens refusing to be distracted by the Lycra-clad bottoms just to the right of his eyeline. I would have to move desks. Probably offices.

[5] I have a hand-woven motif of an Aztec eagle I bought in Mexico last year, in my living room at home. This was before either Shamanic ceremony.

[6] E.F. Schumacher wrote a book in the early 70’s called Small is Beautiful, criticising the ‘bigger is better’ attitude of mainstream Western economics; that natural resources should be conserved; and that capitalism brought higher living standards at the cost of deteriorating culture (and he never had the benefit of a field trip to Dubai). Dismissed as socialist nonsense by many at the time, his work is now taken seriously.

[7] I will admit that this wasn’t always the case – through my 20s I had a couple of pairs that read SPANK in fluorescent lettering across my arse.

[8] I’m being reductive for brevity’s sake, but: longboards – easier for beginners, but top riders do use them (they’re seen by some as a purer expression of the art); they’re also required for big wave surfing. Shortboards – quicker, easier to turn, easier to get outside (you can duck under the oncoming wave); but, much harder to find your take-off spot and stay on your feet. Not for beginners.

[9] Again, to keep it simple, there are three types of waves you’re looking out for –

- Lefts: A wave breaking to the left from the perspective of the surfer – good for goofy-foots (left foot back).

- Rights: A wave breaking to the right from the perspective of the surfer – good for regular riders (right foot back).

- Close-outs: a wave that breaks all at once from end to end. You don’t want these; if you accidentally select one, good luck in the impact zone.

[10] ‘Thong-ing up’ is a genuine technique if you’re looking to gain pace on a waterslide. My sister and I discovered this trick one mid-90s summer on the South West coast of France, and as a result, managed some improbably fast descents across European water slides for years. We were aggressive and to be contended with. Our exploits would often incur friction burns, or in the case of one badly rendered concrete flume in Antibes, lacerations. But we didn’t care, being King (and Queen) pin on the slide was all that mattered. A few years later, we took a summer holiday to America, but our fellow park-goers at Wet ‘N’ Wild were–oddly to us–not as game as the Europeans to participate in this unrelenting pursuit of speed at all costs, which very much included one’s dignity.

I also remember wondering why all the women had their bikini tops on. Luckily for me (and my Dad), we went back to France the following year.

[11]I’m aware that this is the life that so many of you daydream about when the kids are screaming, or your boss is being a cunt (deliberately interchangeable).

[12] By the early 90s this must surely have been an anachronism. Absurd, when you consider it would have been considered far more egregious to be an openly gay teacher in 1992.

[13] I’m not claiming to have been able to articulate myself in this way as an eight-year-old; it’s how I translate the memory of those feelings today.

[14] To mildly amuse myself, I included ‘sex’ under ‘What you love’ and ‘What you’re good at’. Perhaps an OnlyFans account is an inevitable next step? I remind myself that it’s this sort of defeatism dressed up as humour that will keep me from progressing. No OnlyFans. Also, to be clear, this is a joke. The six condoms I confidently loaded into my washbag for this trip all remain.